Lt. Commander Kevin Duffy argues that junior officers must be adaptable to any scenario in the shifting security environment the world finds itself in.

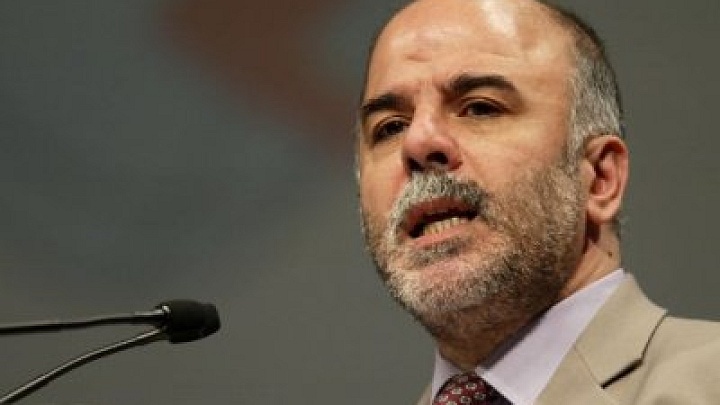

About the Author

Kevin Russell

Kevin Russell is currently a Political Science PhD candidate at Yale University, focusing on constitutional transitions and development of rule of law in the fields of comparative politics and political theory. From 2008 to 2009, he was the governance advisor on a State Department Provincial Reconstruction Team in Taji, Iraq. From 2004 to 2008, he worked in the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), primarily in the Iraq Policy office.