Emma Sky discusses her new book, The Unraveling, as well as ways to fix Iraq and defeat ISIS.

- A Double Dose of Reality on “Homegrown Terrorism”

- How the World Stopped Worrying about Nuclear Disarmament and Forgot about the Bomb

- The Soldier Who Named it Burkina Faso

- Leaders in Transition

- Was Machiavelli Right About Innovation?

- As the Smoke Clears: Tobacco and the US Military

- ISIS Is an Existential Threat, but Not to the West

- A Shattered and Dangerous Land

- War Is Extinct, and We Miss It! Part 3: What Is Our Military Future?

- War Is Extinct, and We Miss It! Part 2: Why Do We Miss War?

- War Is Extinct, and We Miss It! Part 1: What Happened to War?

- Why Are God, Jehovah and Allah Taking All the Blame?

- Women in Combat: Why Now, What’s Next

- The War Aquatic with Nancy Sherman

- Why Are the Religions of the West so Violent?

- The Islamic State Meets the Laws of Economics

- Winning the Peace in Mesopotamia

- A New Image for an Old al-Qaeda

- The Taliban’s Siege of Kunduz Highlights a Worrying New Dynamic

- Let’s Make ISIS a State

- Women in Combat Part 3: Are Women the New Blacks?

- Women in Combat Part 2: Reality

- What’s Haunting Anglo-Iranian Relations

- Going Public: The New Importance of Saudi-Israeli Rapprochement

- Why NATO Intervened in Libya, but Not Syria

- Why Britain hasn’t Followed the US into Syria

- NATO Has Little to Show from its Libya Intervention

- Women in Combat: Can versus Should

- In Iraq, Where There is No Will, There is No Way

- Enemy’s Enemy: Who is Giving America Intel on ISIS in Afghanistan?

- Fiction for the Strategist

- To Catch a Cheat: Trusting the Verification Regime in Iran

- Disarming the Profession of Arms: Why Disarm Servicemembers on Bases?

- Death by Treasury: The Challenge of Defense Austerity in Britain

- Figure Out the Air Force: Airpower, Nuclear Weapons and Next Generation Bombers

- 200 Years after Waterloo, How will Today’s Wars be Remembered?

- Here’s How We Should Think about Intervention

- Why We Don’t Need a New War Against ISIS

- The Fight Within Every Veteran and with Those They Love

- Challenge 2016 Candidates on Long-Term Security Policy

- Vladislav Surkov: The (Gray) Cardinal of the Kremlin

- Is Clausewitz Still Relevant?

- Whack-a-Mole Strategy Against ISIS not Working

- Emma Sky on How to Fix Iraq and Defeat ISIS

- ‘Signature Strikes’ by Drones Are Counterproductive

- The Melting Pot of our Military

- Where’s the Courage of our China Conviction?

- John Boyd’s Revenge

- Should Women Fight Alongside U.S. Special Forces?

- Want to Save the Defense Budget? Kick Those Nasty Habits

- Urban Warfare and Jade Helm: Why We Should Invade Texas

- Thanassis Cambanis on Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution

- Destroy the ‘State’ in Islamic State

- Meeting the Unforeseen: The Need for More Military-Industrial Analysis

- Are We at our Norman Angell Moment with China?

- How to Avoid Future Hadithas

- Time to Squeeze Iran Harder

- America Needs an Open Source Intelligence Fusion Center

- Two Sides of the Vietnam War and its Personal Costs

- Simple Rules and Tools for Modern Leadership

- A Bitter Pill: Fake Drugs and Global Health Security

- UK General Election: ‘There Are No Votes in Defence’

- The NFL’s Phony Patriotism

- Is Afghanistan Turning a Corner?

- House of Cards: How King Salman’s Reshuffling May Backfire

- Fixing Military Intelligence Gathering, but of the Medical Kind

- Iran is no Irrational ‘Martyr State’

- The Battle for Bayji, and the Heart of Iraq’s Oil Industry

- This Week in War

- From Tikrit to Mosul

- Reports of Assad’s (Pending) Demise May be Greatly Exaggerated

- Special Relationship: U.S. Marines Flying from a UK Warship

- America’s Failed Revolution

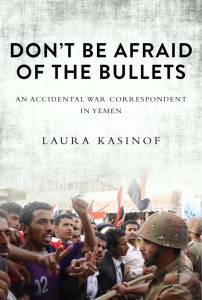

Laura Kasinof on Being an ‘Accidental War Correspondent’

By The Editors

Just moments before our interview, Laura Kasinof heard the news of Steven Sotloff’s killing by ISIS rebels. War reporters in the Middle East form a close-knit group. But some have asked: Why do they do it, and is it worth the risks? In her upcoming book, Kasinof describes her time spent in Yemen as a reporter covering the violence of the Arab Spring.

So after spending years in Yemen, are you afraid of bullets?

There were times when I was around so many Yemenis who are not afraid of gunfire the littlest bit and that bled over to me. When you put yourself in dangerous situations over and over again, your body does not become as frightened, almost as a survival mechanism. The title [of the book] comes from a phrase Yemeni protesters would say at demonstrations when government forces would attack them. The groups of Yemenis would walk straight toward the gunfire.

You open with this vivid scene of a government massacre. One looming question over the Arab Spring is why some nonviolent protests turned violent whiles others didn’t. Why didn’t places like Libya, Syria, or Yemen turn out like Tunisia?

In Yemen it’s a different story than what happened in Syria and Libya, or even Egypt. In Yemen, protesters really maintained a desire to be peaceful and at most throw rocks. There was a rebel army commander who split off from the government and that brought conflict to the capital. But protesters themselves stayed peaceful. Yemenis know conflict because there is a traditional dispute mechanism to resolve conflicts between tribes where they’ll try to mediate but also will fight.

You describe this honor system that exists in Yemen. Anthropologists describe similar honor codes, in Appalachia and other rural places that have seen violence. How did honor influence the conflict in Yemen?

You describe this honor system that exists in Yemen. Anthropologists describe similar honor codes, in Appalachia and other rural places that have seen violence. How did honor influence the conflict in Yemen?

It’s anomalous, for lack of a better word, what happened in 2011 when government soldiers shot dead unarmed protesters. Stuff like that never happened in Yemen before. Was it because of war’s dehumanization? Was it for political reasons? I always felt safe in Yemen because I truly trusted nobody would shoot a foreigner unless they were al-Qaeda. In Egypt, people were wielding guns for the first time, and [there was] no code of who you could target.

You mention that in the north nobody shoots to kill but rather they aim their weapons above their target’s head. It’s about “machismo,” you write. This is fascinating. President Saleh almost violates a sacred code of how Yemenis are supposed to fight their civil war and that’s what seems to enrage everyone.

Right, the political activism and demonstrations weren’t that large in Sana’a. But people came out to Change Square because that honor system was broken. You just don’t shoot an unarmed person in the head in Yemen. The government went to great lengths to place blame on other people, but there is video evidence that soldiers were shooting unarmed protesters. I talked to a British guy who had lived there a long time, and like 20 years ago he was kidnapped for a day and he was being held by one tribe and another tribe wanted him for ransom and he told me for an hour there were mortar shells and RPG fire, and no one was killed after an hour. It was who made the most noise.

Just being around gunfire, the first time I was terrified. The second time I was less terrified. Then you just don’t believe you will be shot.

That’s crazy. At one point you describe war reporting as “fun.” We heard similar comments made in the discussion after James Foley’s death over why reporters do it. is it exhilarating?

There was not a precedent for [kidnapping] happening then. It’s a much greater threat now than it was then. Nobody had been kidnapped [when I was there]. I covered up outside Sana’a. At that point there had never been a mass bombing like we saw in Iraq or Pakistan.

What about after U.S. drone strikes? Did you get any harassment for being an American?

I was never scared about being an American in Yemen. Just being there is what gave me that trust. There were times I was scared from being in the wrong place at the wrong time. One time in particular I was taken advantage of for being a woman. In general, just being around gunfire, the first time I was terrified. The second time I was less terrified. Then you just don’t believe you will be shot. A soldier would get in so much trouble if he killed a foreigner. So I started doing stupid things because I got less scared. It’s a natural defense mechanism of your mind.

You say you like to work alone. But isn’t it more dangerous, especially as a woman in a place like Yemen, to work alone? At one point you noted a thought that ran across your mind in reconsidering your lack of headscarf: “Do I look like a whore?”

So in general I found it easier as a woman because Yemen is such a traditional society. Nobody would ever just shoot a woman. There’s not really rape outside family to family [interactions]. If they got caught the man would just get in so much trouble. So women are protected, but you have to wear a big black hijab and be kept away. As a Western woman that didn’t apply to me. I could dress however I wanted. I did not wear a hijab when I was [in Yemen]. The only time I ran into a trouble for being a woman was with people who were very Americanized, or who had lived in the States and thought all American girls are complete sluts. They were also very wealthy men who had high position within Yemeni society and were close to the president.

You have this great line: “Yemen, oh Yemen, she dances to the rhythm of her own drum, with many parts still untainted by influence from the Western world…Yemen was like walking into a world that I previously didn’t know existed. A world that I was soon to learn was still full of guns and daggers, of arranged marriages and antiquated caste systems…Everything in this country implied violence. Their dress, the call to prayer, the need for military checkpoints on the way into the city from the airport. I wondered why my friends loved it here so much.” So why did you move to Yemen?

I just wanted to move someplace new and was debating Syria or Yemen. There’re no freelancers in those countries, so not much competition. This was in 2009. I decided I would get kicked out of Syria. Yemen was cheap. I ended up falling in love with it. It’s so fun and you feel so blessed in a place that runs by an old traditional code of laws. It does not feel like a capitalist society. It’s really relationships that drive things in Yemen, because it’s so isolated. I just fell in love with that aspect of it. But in the end I had to leave because everyone knew my business and I knew everyone else’s. I knew who they were cheating on their wives with. I felt I was part of system and I got too intertwined in Yemeni society.

How did you initially get the New York Times to, in your words, take a chance on an “inexperienced twenty-five-year-old girl”?

I’d worked for them in Cairo for a little bit. I interned at the bureau, in 2010. When protests [broke out in 2011] I emailed Michael Slackman and said, ‘Do you want to use me?’ I was always co-authoring stories. But then as the year went on they started to let me have my own byline.

So by law, all articles and interviews tangentially about Yemen have to mention qat. You discuss it often in your book. How has it influenced the war in Yemen?

It is unbelievably consumed. The stat is that 90% of men chew qat every day, which seems to be about right. Definitely the conflict always stopped every afternoon for qat time, except for the worst phase of [the violence]; between 1 and 6pm there would be no fighting. The airlines started flying into the airport at that time of day because the war was near the airport. They used to always come in the middle of night but switched to the middle of afternoon because they knew [there would be] no artillery fire then. [Yemenis] will eat food that prepares their stomach for qat. So it’s all this big to-do and ritual. The chewing settles your stomach and helps your digestion. You get really hyper but then after the second hour you start to calm down. Then you can fall asleep. Why don’t they fight while they’re hyper? It’s a sacred time of day. Even soldiers shooting at one another would stop and then chew qat together.

That sounds like the norms of reciprocity in the World War I trenches described by Robert Axelrod. Speaking of which, you describe graduate school, which you dropped out of, as a waste of time. I’m shocked by this and insulted.

[Laughs] I sometimes still want to go back to grad school. But at that time of my life it was a waste of time. I was just too eager to be out in the field. I will not say that grad school is a waste of time for everyone.

It seems like you let the war definitely affect you as a person. We heard of journalists being objective and see bylines and assume they are these wooden statues dutifully taking notes but not taking sides. But you at one point broke down sobbing. Can you describe what it was like, in your role as a person witnessing atrocities and wanting to probably intervene versus your role as a journalist who is not supposed to be the story and just record what is happening?

My reaction to the atrocities that I saw being used against the Yemeni protesters, wasn’t so much to intervene, but to report. Because what else could I do in the moment? I’m not a doctor. I can’t stop the shooting. So in the moment reporting feels like a service. And also I will say that I never broke down totally in the moment. That happened afterward. There was the feeling that I must stay strong so that I could do my job. At the end of the day it still ended up taking a toll on me, but it was more of a delayed reaction. It’s tough, but it was also so rewarding to be around people living in the moment of conflict. I think that’s a big driving force why I did it.

Laura Kasinof is a freelance journalist whose work focuses on the Middle East. From 2011-2012, she reported for the New York Times from Yemen, covering anti-government protests and conflict that was part of the political upheaval unfolding across the Arab world.

Laura Kasinof is a freelance journalist whose work focuses on the Middle East. From 2011-2012, she reported for the New York Times from Yemen, covering anti-government protests and conflict that was part of the political upheaval unfolding across the Arab world.

Don’t Be Afraid of the Bullets: An Accidental War Correspondent in Yemen

Arcade Publishing, 302 pages, $18.60

Related Posts

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon discusses her new book, Ashley's War, as well as the challenges women face as they look to join and fight alongside U.S. Special Forces.

Journalist Thanassis Cambannis discusses his new book Once Upon A Revolution and elaborates on the missed opportunities of Tahrir Square, the military regime's...

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon discusses her new book, Ashley's War, as well as the challenges women face as they look to join and fight alongside U.S. Special Forces.

Journalist Thanassis Cambannis discusses his new book Once Upon A Revolution and elaborates on the missed opportunities of Tahrir Square, the military regime's...

Leave a Reply (Cancel Reply)

Popular Posts

-

Is the Marine Corps Setting Women Up to Fail in Combat Roles?

February 18, 2015 -

Women in Combat: Can versus Should

August 10, 2015 -

The F-35 Was Built to Fight ISIS

October 13, 2014

Recent Comments

- search Grand Prairie auto insurance quotes on Christopher Coker on Prospects for a Great Power War

- search Alexander City auto insurance quotes on Enemy’s Enemy: Who is Giving America Intel on ISIS in Afghanistan?

- 3 Simple Reasons Why Torture Is Still Wrong | KJOZ 880 CALL IN TOLL FREE 1-844-880-5569 on A Former U.S. Army Interrogator on Why Torture Doesn’t Work

Cicero on Twitter

@DanKaszeta @CarlDrott Definitely! It'd be great to see an article of yours on Cicero again.

Arnold Isaacs reviews Peter Bergen's "United States of Jihad" and Scott Shane's "Objective Troy" for Cicero Magazine ciceromagazine.com/r…

Arnold Isaacs looks at recent two books which are straight-talking about the realities of "homegrown terrorists" ciceromagazine.com/r…

Arnold Isaacs reviews Peter Bergen's "United States of Jihad" and Scott Shane's "Objective Troy" for Cicero Magazine ciceromagazine.com/r…

.@ChrisMMiller80 examines the nuclear weapons debate, how it could be achieved and whether it would be a good thing. ciceromagazine.com/f…

Is a world without nuclear weapons a safer world?ciceromagazine.com/f… … @BlogsofWar @RCDefense #NuclearDeal #IranDeal #NuclearPower

.@ChrisMMiller80 looks into the nuclear weapons debate & whether we should talk about "disarmament" or "abolition." ciceromagazine.com/f…

Blogroll

- Government Executive- Defense

- The Monkey Cage

- War on the Rocks

- Task and Purpose

- The Long War Journal

- Political Violence at a Glance

- Duck of Minerva

- Just Security

- Lawfare Blog

- Small Wars Journal

- Phase Zero

- Overt Action

- The Bridge

Tags

© Copyright 2016. All rights reserved.